Originally published on:

http://adage.com/article/agency-news/brian-wieser-quoted-man-advertising/310173/

When Brian Wieser strolls the Palais during the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, he flies under the radar. “I’m not a celebrity in the industry. I’m definitely B-list,” he says.

While he may go unnoticed at industry events, his analyses are anything but unheeded. When Pivotal Research analyst Wieser speaks, everyone from small investors to holding company titans like WPP’s Martin Sorrell listen. His recommendations and reports can lift or sink an advertising or media company stock.

Just ask Snap. When the company launched its initial public offering on March 2, trading opened at $24. That very day, Wieser valued the stock at $10, saying it was “significantly overvalued given the likely scale of its long-term opportunity and the risks associated with executing against that opportunity.” Poof went the price: Snap shares as of mid-August traded around $13, down nearly 46% from the opening.

Still, Wieser doesn’t put much stock in his influence, saying lots of share price moves get attributed to analysts, and it’s hard to tell how meaningful those shifts are or to specify what source caused them.

It all points to Wieser being a remarkably unassuming guy who can talk a blue streak about valuations but is far from comfortable discussing himself.

“A profile on me?” he asks incredulously during our first phone interview.

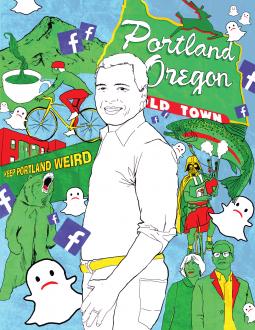

Wieser doesn’t work out of a cushy office on Wall Street; he operates out of Portland, Ore., where he lives with his wife, Amy Edwards, and two kids, Alex and Brooke, age 7 and 9. He’s Canadian by birth, and his ambition, says 43-year-old Wieser, is to form an “early ’80s post-punk, French new wave cover band.”

Wieser is described by his friends, followers and peers as “chill,” “quiet” and a “genuinely super nice guy,” who just also happens to be respected, if not feared, for his reports—which don’t always take the expected turn.

Many investors were breathless over Facebook’s stock, which rose 50% this year, when Wieser poured cold water on the valuation. “Despite a decent 2Q17 and an outlook that appears consistent with our expectations, we are downgrading Facebook from Hold to Sell given the stock’s remarkable run this year and a current price that is now 19% over our price target as of Friday,” he penned. The July 31 report was issued just a few days after Facebook stock hit its all-time high of $175.49. Wieser valued it at $140.

The move sparked over 100 news stories with headlines like “Facebook Receives an Incredibly Rare Sale Call” and “Meet Facebook’s New Skeptic.” (As of this writing, Facebook was trading at about $170.)

From Radio to Rock to Wall Street

During his time at the University of British Columbia, Wieser worked for his college radio station, where he developed a program modeled on CNN’s “Crossfire” in 1992 named “Get in the Ring.” A year later, he decided the show should be streaming, so he tried to get the station on the “pre-web internet,” which he says was a fun adventure, but he couldn’t get it to work. He did, however, put the station’s print magazine online.

In addition to his radio show, Wieser helped organize one of the largest hip-hop festivals in Canada at the time—DJ’s Sound War. It was dubbed the biggest hip-hop festival west of Toronto and north of San Francisco, with more than 1,000 attendees.

Next, Wieser went to the University of Western Ontario Richard Ivey School of Business to earn his MBA, and his love of music went with him. He had his own band, the Tonebursts, and played with Bossanova for a while—a separate project with many of the same people from Tonebursts—that’s still in existence today. Wieser says being a full-time musician would be a “little too repetitive for my taste.” Though he did, he says, “gain and maintain an appreciation for the craft of performing and the beauty in the details,” which he compares to writing where “every word matters.”

Wieser sarcastically jokes that the transition from radio to investment banking is a “natural progression.” He did rotations in both media and entertainment at his first post-MBA job as an investment banker at Lehman Brothers in New York City, but in 2002, the economy got tough. Wieser wanted to stay focused on the media industry, but no opportunities were available, so he moved to Deutsche Bank to cover the cable industry as a research analyst.

Not only does Wieser say he enjoyed his time on Wall Street, he says he also learned an important lesson: “Never trust a number unless you’re sure the number you’re working with is provided by someone who could go to jail if that number is wrong. This is so important because people will take numbers and pass them for facts without understanding where they came from.”

He took this lesson with him when he joined the agency world, he says, making sure to ask people to present hard facts rather than assertions around topics or concerns, such as the death of TV because DVRs were invented. “There was no reason to believe that this death was happening,” says Wieser.

One year after joining Deutsche Bank, Wieser connected with a headhunter, who told him that Interpublic Group was looking for someone to replace the legendary Robert Coen, who spent 60 years at the holding company as a forecaster. “It sounded like a compelling job, knowing nothing about advertising,” says Wieser, who succeeded Coen as global director of forecasting at Magna, a division of IPG Mediabrands.

“That essentially is what got me into the advertising world,” says Wieser. “It was like an extended PhD, albeit a paid one, where I touched a lot of different parts of the agency world, with a core focus on understanding how advertisers make decisions and how they think about budgeting.”

Nick Brien, who was CEO of IPG Mediabrands at the time, says Wieser was influential even then. “His ability to be stubborn and dogmatic are legendary,” says Brien, pointing out that Wieser actually changed the way Magna reported spending. Wieser, he says, thought reporting an advertiser’s global ad spend was “too vague” since it’s hard to track where certain dollars go when it comes to things like production costs or agency services, so he had Magna calculate growth and estimated spend based on revenue instead.

That restlessness and passion are what make his analyses so thorough, says Brien, who recently changed jobs from global CEO of iCrossing to chief executive of Dentsu Aegis Network Americas and U.S.: “Everyone cares about what [Wieser] says.”

Wieser left to join Simulmedia in early 2011 because he believed in the ad tech company’s concept of behavioral and personal targeting, and it was then he relocated to Portland, where he says “young people go to retire.” Wieser became a senior research analyst at Pivotal toward the end of 2011, noting that working remotely for Simulmedia became difficult, and that he also missed the bigger-picture trends in advertising.

Today, Wieser churns out three to five reports in a slow week, but during busy times, pens upwards of 15, covering topics like TV viewing trends, holding company earnings reports, media agency billings, ad and marketing tech tools and brand safety. His reports—depending on how much time he has—range from straightforward and scholarly to snarky and fun, with titles like “IPG, OMC, PUB, WPP: ANA Production Transparency Report Released” versus “Of Beer, Chocolate and the Commoditization of Ad Tech.”

‘Portlandia’ Isn’t a Satire, It’s a Documentary

“Portland is something of an outpost,” says Wieser. “There’s an advertising industry here, some marketers, not as many media owners. It’s not a big market, but I think it’s a practical matter—I can make time to get things done and go to Cannes and different industry events, and it’s easy enough to go back to New York once a month.”

The laid-back nature of Portland is a draw for Wieser, who says it reminds him of growing up in Vancouver. And he appreciates the microbreweries, the fact that people are “very aware” of their athletic brands—think Nike versus Adidas and Under Armour—and the city’s dedication to craft, whether it’s coffee, food or wine. (Yes, he watches the TV series “Portlandia,” and jokes that the show “isn’t a satire; it’s a documentary.”)

While he may have one foot on the West Coast, Wieser stays plugged into the industry by attending all its big events including Cannes, Dmexco and CES. Last year, he was over the Diamond Line for Delta with 125,500 SkyMiles.

Sorrell tells Ad Age he reads all of Wieser’s reports, whether they’re on macro trends, holding company news or media insights. “He’s exhaustive—he covers everything. And you can spend your life reading him, like going to conferences,” says Sorrell via email. “He has good insights most of the time and he cares.”

Dave Morgan, founder and CEO of Simulmedia, who hired Wieser as chief marketing officer after his tenure at Magna, says he reads Wieser’s reports the second they hit his inbox. “He’s extraordinarily smart and consistent to a fault,” says Morgan, adding that Wieser has an uncanny ability to be persuasive.

Several times, Morgan says a client would have a strong point of view on a particular topic that Simulmedia knew was incorrect. “I’d just turn it over to Brian,” he says. “He doesn’t cross-examine—he just logically works people down to the final issue in an extraordinary, friendly way.”

Where does creativity come in?

Few people have anything bad to say about Wieser—or at least no one would go on the record with Ad Age, which could either be an endorsement of him or a function of being unwilling to upset the analyst publicly (most agencies are public companies that cannot offer commentary on analysts who cover them).

Still, if there’s one chink in Wieser’s armor, it may be creativity. At a time when its role in an agency’s valuation is in the news—and whether awards like Cannes enhance or detract from the bottom line (paging Publicis Groupe’s Arthur Sadoun)—some think Wieser should put a bigger emphasis on the work.

“Creativity is the foundation of our industry and there’s nothing more valuable at a time when disruption is rocking everyone and everything,” says Andrew Bruce, CEO of Publicis North America. “When we redirect creativity from filling channels to finding solutions, a new world of possibility emerges. Is there a more powerful tool than creativity at a time like this? I don’t think so.”

Wieser isn’t arguing with Bruce’s assessment. He says he tries to connect observed behaviors on spending outcomes and it’s hard to show a correlation between successful creative products and business success.

“If agency holding companies would provide more disclosures, I’d have more to work with,” says Wieser. “We work in a world where we don’t know what we don’t know and we make educated guesses based on available data.”

To make sure he’s well-informed, Wieser—in addition to doing his own research—reaches out to colleagues and peers to discuss topics of interest. Matt Spiegel, managing director and head of the data and technology solutions practice at MediaLink, says he meets up with Wieser at industry events several times a year to exchange stories. Spiegel even sometimes gets emails from Wieser with questions about analyses he’s working on.

Jay Haines, founder of Grace Blue, who has known Wieser for about four years, says he’s always impressed with the well-rounded and balanced nature of his reports. And that balance is something Wieser instills in his own life, too. He manages to do CrossFit three to five times a week, while maintaining his self-proclaimed status as a chocoholic. This year after Cannes, Wieser visited 15 chocolateries in France in one day.

“Brian is a really interesting character with an enormous intellect,” says Haines. “He understands the needs of the streets and the needs of holding companies. He’s almost become a brand in his own right as a barometer for the industry.”

Not bad for a failed Canadian new wave rock star.