Originally published on:

http://adage.com/article/cmo-strategy/chief-marketing-outsiders/310889/

Sicily Dickenson was on vacation last year when she got a call from a recruiter. The 10-year veteran of energy companies, most recently power company NRG Energy, was surprised to hear the job being pitched was chief marketing officer at Mattress Firm. “I was like, ‘That’s weird, I’m a renewable energy kind of girl,'” Dickenson says. But after dining with the executive team, the motivation became clear. “They thought I would bring to the culture something positive in a company where outside hires are few and far between.”

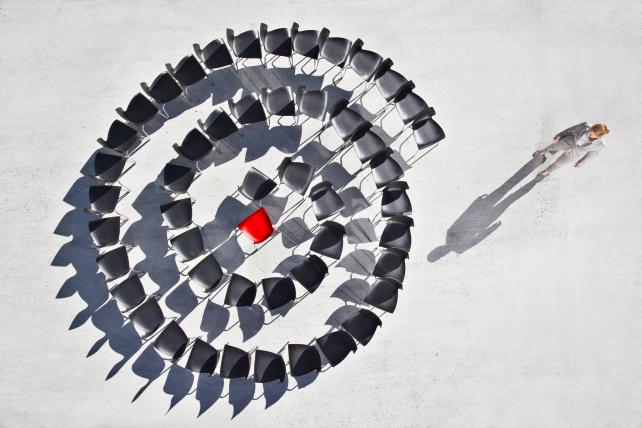

At marketing departments across America, outsiders are in and insiders out. While CMO turnover has been rising for years, open posts are filled by people from outside the company, even if it means hiring a CMO with zero experience in the industry in which their new company competes.

Consider these job jumps within the past year: The new CMO at Dunkin’ Donuts spent the bulk of his career at ad agencies. Ancestry.com brought in a marketing leader with more experience in baby care and cosmetics than genetics. Parka-maker Canada Goose went even further afield, tapping a former Ultimate Fighting Championship executive.

In a recent report, executive recruiting firm Russell Reynolds Associates calls it a “CMO succession crisis,” suggesting that “succession planning continues to be a major challenge for most businesses.” The trend, it says, also implies that the “aspiring next generation CMO leaders will need to change employers to reach the next level of their career.” External hires represented 72 percent of all CMO appointments in the first two quarters of 2017, up from 64 percent in the year-earlier period and 63 percent the year before that, according to the firm, which tracked 187 marketing-leader moves in the first half.

The external replacement rate has been in the 70s before, but it may be more likely to stay there now: Industry experts see it as a necessity, not as a crisis. CEOs are increasingly responding to shifting business dynamics that call for an entirely new skill set from CMOs, they say, and an equal aptitude in data analytics and traditional brand-building skills.

Marketers say, “‘We need someone who really understands modern consumers,’ as opposed to ‘Let’s hire another guy in the likeness of the previous three guys,'” says Jay Haines, founder of headhunter Grace Blue. “The companies are saying, ‘Our consumer is evolving, and the fix is a new way of marketing to attract and retain this new breed of consumers.'”

So CMOs keep getting pushed overboard. On average, a CMO at a leading U.S. consumer brand spends 42 months in the role—a 13 percent decline since 2014, according to a recent annual report from consulting firm Spencer Stuart.

Also helping to fuel the trend: CEOs are looking for ways to demonstrate a willingness to evolve during a time when shareholders and activist investors are pressuring companies for larger, faster returns.

Fault lines and swim lanes

While the CMO’s job is evolving, he or she is still held accountable for growth. And right now, growth is hard to come by. Last year, 259 companies in the Fortune 500 had declining revenue, and 239 of those companies had declining after-tax profits, according to the Association of National Advertisers.

“That’s saying we’re not succeeding as an industry,” says ANA CEO Bob Liodice. “However you want to blame it, whether it’s the marketer’s fault, the agencies’ fault, the media’s fault, or whoever’s fault it is, the ecosystem isn’t working. You can’t just keep firing agencies and firing media companies. It’s kind of like a ball club—you go fire the manager. And that’s what’s happening as managers, in the form of CMOs, are getting fired.”

But it’s not that easy to find replacements who meet today’s business demands. “Marketing has become a series of highly specialized subdisciplines, and the days of being a generalist are almost gone,” says Richard Sanderson, co-leader of the marketing officers practice at Russell Reynolds. He equated today’s career paths with a series of strictly defined swim lanes, each one focused on a particular skill, like creative, innovation, insights or trade channel marketing, to name a few. “The challenge is you don’t see many marketers through their career be rotated through different subdisciplines and have that broader, rounded training that makes them ready to take on a senior leadership role,” he says.

A report published last month by the ANA suggested that “college and university curricula cannot keep pace with the rapid change going on in the industry.” Says Liodice: “I’ve heard for years and years about how talent is a marketer’s top priority, but it seems to be mostly talk and not a lot of action. For the balance of the industry, training and development is not at the uppermost of their minds.”

To get ahead today, employees often must take charge of their own growth—and be willing to change jobs to gain new skills—rather than rely on internal training. “It’s always best for the individual to really take accountability,” says Kristi Maynor, who heads the U.S. chief marketing officer practice at executive search firm Egon Zehnder.

It’s hard to convince chief financial officers tasked with keeping a tight budget that internal marketing training programs are worth the cost, recruiters say. Some companies would rather invest in bringing in big-name hires from the outside rather than train existing employee candidates.

“A lot of companies are not convinced that marketing has a great ROI,” says Laura Keller, founding partner of Pixie Dust, an executive recruiting firm specializing in marketing and communications. Conversely, “If you’re going to groom a sales team, that has concrete deliverables and a great ROI.”

Some sectors are especially ripe for turnover. For instance, in retail only 45 percent of marketing appointments came from inside the industry in the first half of 2017, compared with 73 percent in the six months prior, Russell Reynolds found. That’s because retail is undergoing rapid change, as e-commerce slowly eats into brick-and-mortar traffic and shopping habits change. For CMOs, relationships with merchandising and operations departments traditionally meant the most, but today executives must build bridges with chief information officers and chief financial officers, according to a Russell Reynolds report called “From CMO to C-Uh-Oh.” Working across the C-suite is “a very different skill than simply evaluating a TV campaign’s impact on branding,” the report says.

For Canada Goose, the Canadian apparel brand, hiring an outsider was key to expanding beyond its parkas with the recognizable patches. Last year, the Toronto-based brand brought on Jackie Poriadjian- Asch as CMO from Ultimate Fighting Championship, where she was head of global brand marketing.

While Canada Goose has blown up in popularity beyond its northern roots, the brand is boosting its U.S. presence with a direct-to-consumer e-commerce site and stores after decades of wholesaling.

At UFC, Poriadjian-Asch spearheaded the development of a digital streaming service called Fight Path to directly communicate with customers and make the group less reliant on distributors such as DirecTV, Comcast and Time Warner. Canada Goose found her experience analagous as it, too, expands beyond third-party distributors. Poriadjian-Asch says her lack of a retail background is a plus in that she can build up the company’s marketing approach.

“Most traditional fashion or sportswear [brands] are still bogged down by a legacy of television … billboards or print,” she says, “but Canada Goose has given me the ability to start from a blank slate and build this in the right way—highly digital for the modern consumer.”

Wake-up call

Mattress Firm looked outside for a CMO after executives realized the brand’s placid marketing department needed a jolt in order to compete with newer rivals such as innovative e-commerce competitors Casper and Tuft & Needle. The company, which for two decades operated a simple business selling beds in Houston, in recent years expanded via acquisitions to become a national player with 3,500 locations and $4 billion in revenue.

With Dickenson, it got the shakeup it wanted.

Earlier this spring, she hired the brand’s first creative agency—and not just any agency, but Droga5—to spearhead a product campaign that kicked off with a live keynote from Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak touting “the most important tech reveal of 2017.” The humorous effort was in stark contrast to the company’s price-driven hard sells of the past.

Dunkin’ Donuts did not respond to requests to discuss why it went outside the company to find a CMO. In September, when it hired former DigitasLBi North American CEO Tony Weisman as its U.S. CMO, the coffee and donut marketer cited his “data-driven approach to marketing” and “extensive digital acumen.” Weisman made the leap after a career of climbing the ranks at agencies, including 10 years at DigitasLBi and 19 years at Leo Burnett.

Hiring an external player rather than promoting internally could also send a message that change is coming to investors via business media coverage, especially when that brand is struggling, recruiters say. Dunkin’ saw second-quarter revenue increase just 1 percent to $218.5 million.

Avon to Ancestry

Tech companies are especially averse to promoting from within. In the first half of the year, 89 percent of the CMO appointments in the sector came from external companies, according to Russell Reynolds. One of the hires included Vineet Mehra, who was named CMO at Ancestry.com, which uses DNA and historical records to build family trees. He came from packaged-goods giant Johnson & Johnson, where his roles included global president of baby care and president of global marketing services. Before that he was global VP of cosmetics and color at Avon.

Mehra says tech companies like Ancestry are looking to the outside as they grow and can no longer rely on performance marketing, which refers to more transactional online ad methods targeting sales, leads or clicks. So they must bring in marketing leaders with broader brand-building skills.

“It was all about last-click acquisition, performance marketing. But what you are starting to see is that you need to combine performance marketing with brand marketing and you need to put those two together,” he says. “What CPG companies are realizing is they don’t have people in their house that can do the performance side, and I think tech companies are realizing they don’t have scale leaders and brand thought leaders.”